Report On Public Guardianship

Ten Year Review & Recommendations

Massachusetts Guardianship Policy Institute

2025

Table Of Contents:

Executive Summary

REPORT OF THE MASSACHUSETTS GUARDIANSHIP POLICY INSTITUTE

The First Ten Years: Review and Recommendations

The Massachusetts Guardianship Policy Institute was established in 2014 to address the critical lack of decision-making support for Massachusetts’ most vulnerable and indigent individuals, often referred to as “unbefriended” or “unrepresented, at risk.” This report reviews the first phase of our work. The individuals at risk, estimated to number between 3,000 and 4,000 statewide, face significant risks to their health, safety, and well-being due to decisional incapacity and a lack of financial or social resources.

The Institute’s initial focus was on advocating for the creation of a Public Guardian in Massachusetts. This report examines various models of public guardianship implemented in other states, including government-operated programs (e.g., Illinois, California, Colorado), privatized systems (e.g., Florida’s non-profit network), private appointments originated by public agencies (e.g., Washington, and limited programs in Massachusetts’ DDS and DMH), and privately funded initiatives (e.g., Public Guardian Services in Braintree).

The report argues for the establishment of a Public Guardian in Massachusetts, highlighting the significant individual and societal benefits demonstrated by successful programs in other states. Case studies, such as that of Richard D., illustrate how professional guardianship can stabilize individuals experiencing homelessness and severe mental illness, leading to improved quality of life and substantial cost savings in emergency services and institutional care. Economic analyses from Connecticut and New York further support this, showing potential savings of tens of thousands of dollars per person annually through effective guardianship programs.

Drawing a sharp contrast, the report critiques the current guardianship system in Massachusetts, which heavily relies on an underfunded and often unsustainable volunteer/pro bono model. This reliance frequently results in limited commitment and inadequate support for unrepresented individuals, leading to instability, repeated crises, and costly short-term placements. The procedural complexities introduced by the Massachusetts Uniform Probate Code (MUPC), while intended to protect vulnerable individuals, have inadvertently exacerbated the shortage of pro bono guardians.

The authors emphasize the need for “person-centered” guardianship, characterized by understanding the individual, involving them in decisions, utilizing planning tools, spending meaningful time, adhering to court oversight, and seeking continuous improvement. It outlines the multifaceted roles of a guardian (decision-maker, advocate, quasi-social worker, and even friend) and how the specific circumstances of an individual’s incapacity significantly impact the guardian’s approach.

Looking to the future, the report notes the historical challenges of achieving consensus and reform in Massachusetts guardianship policy. It also acknowledges emerging international human rights perspectives that advocate for a “social model” of disability, emphasizing societal responsibility in providing supports to enable individuals to make their own decisions.

The report identifies hopeful signs that guardianship policy is moving forward in Massachusetts, including the opening of the Office of Adult Guardianship and Conservatorship Oversight (OAGCO), which is providing crucial data on the scope of guardianship in the state. The report also highlights the work of Public Guardian Services (PGS), a privately funded pilot program sponsored by the Institute, which has demonstrated for several years the effectiveness of a professional, social-work model of guardianship for unrepresented individuals.

Findings

The primary conclusions of the report are that the current system for providing guardianship for unrepresented, at-risk individuals in Massachusetts is inadequate, and that the poor outcomes are unaffordable, both financially and in terms of human well-being.

The report strongly recommends the establishment of a robust, publicly funded Public Guardian, that will bring professionally qualified, trained and supervised personal, and much- needed leadership, to the complex issues of guardianship statewide. This system should:

- Adopt a professional, “social-work” model of guardianship that prioritizes person- centered care and comprehensive support.

- Secure dedicated and sufficient long-term funding to ensure the sustainability and effectiveness of the program, recognizing the significant potential for cost savings in other areas of public expenditure.

- Learn from successful models in other states and adapt best practices to the specific needs of Massachusetts.

- Foster collaboration and leadership among guardianship stakeholders to promote a unified and effective approach to policy reform.

- Consider the long-term implications of policy decisions, avoiding unintended consequences that could further disadvantage vulnerable individuals.

The Institute believes that establishing a well-designed Public Guardian system in Massachusetts is a crucial step towards ensuring the dignity, safety, and well-being of our most vulnerable citizens. It also represents a fiscally responsible and morally compelling investment in our people and our communities.

REPORT OF THE MASSACHUSETTS GUARDIANSHIP POLICY INSTITUTE

The First Ten Years: Review and Recommendations

INTRODUCTION

The Massachusetts Guardianship Policy Institute formed in 2014 to provide renewed focus on the guardianship system in Massachusetts, particularly as it impacts individuals who don’t have financial or social resources to provide essential decision‐making support. These at‐ risk individuals may be referred to as the “unbefriended,”1 or as “unrepresented.”2 As both terms suggest, these are people with decisional incapacity who are indigent, isolated and vulnerable. The Institute was established to explore the potential for a public guardian that would address the decisional needs of this population in Massachusetts.3

The initial aims of the Institute were to engage with guardianship stakeholders in Massachusetts, create a forum for public discussion, and develop ideas and strategies for establishing a public guardian. Our first five years of public engagement4 are reported in our first Annual Report.5

One of the first actions of the Institute was to commission research to assess how many people may need a Public Guardian in Massachusetts. The result indicated that there are between 4,000 and 5,000 unrepresented persons at risk due to significant decisional impairment.6 An estimated 1,200 of these individuals have guardians through separate programs managed by the Department of Developmental Services (“DDS”), the Department of Mental Health (“DMH”), and the Executive Office of Aging and Independence (“AGE”7), leaving between 3,000 and 4,000 such individuals in Massachusetts to fend for themselves.

The problems of inadequate decision‐making support for large numbers of persons in need is not unique to Massachusetts. The 2022 Final Report to the Colorado Legislature issued by the Colorado Office of Public Guardianship defines the problem concisely and accurately:

We also have included an excerpt, “General Trends and Factors Impacting the Need for Public Guardianship,” from the 2022 Final Report, edited to provide figures and factors for Massachusetts. See Appendix A.

1 Moye, J., et al., Ethical Concerns and Procedure Pathways for Patients Who are Incapacitated and Alone, HEC Forum DOI 10.1007/s10730‐016‐9317‐9 (published online), p. 4 (Jan. 13, 2017.

2 While both “unbefriended” and “unrepresented” are commonly used to refer to the population of concern to the Institute, we use the latter in this Report, as being more technically correct and less distracting than the other, more emotive term. In using the term, we do not intend to imply anything about legal representation.

3 Unrepresented persons at risk would include those who are isolated by homelessness, untreated chronic illness, drug addiction, repeated incarceration, financial predation, severe hoarding and other vulnerabilities caused by cognitive, emotional or physical incapacity, and who cannot access help without a fiduciary to act with or for them.

4 The following public programs were sponsored and promoted by the Institute in 2015, 2016, 2017 and 2018:

Event

Date

Description/Title

Colloquium

November 10, 2015

Colloquium on Public Guardianship

Colloquium

June 13, 2016

Colloquium on Volunteer Guardianship in Kansas

Open Meeting

September 15, 2016

Meeting with the Florida Office of Public and Professional Guardians

Colloquium

November 16, 2016

Colloquium on a Proposed Public Guardianship Statute

Colloquium

July 21, 2017

Colloquium on Public Guardianship in an Age of Self‐Advocacy

Public Conference

December 6, 2017

A National Perspective on Guardianship and Decisional Support

Public Conference

November 27, 2018

Decision‐Making: Balancing Autonomy and Risk

Public Conference

November 6, 2019

Abuse and Self‐Neglect

5 The Massachusetts Guardianship Policy Annual Report 2019‐2020 can be read and downloaded at http://18.209.103.195/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/GPI-Annual-Report-19-20.pdf

6 See Moye, J., Catlin, C., Wood, E., Teaster, P., & Kwak, J. (2016). Examining the need for a public guardian in Massachusetts. Published at https://guardianshipcenter.org/research‐studies/publications/examining‐the‐need‐ for‐a‐public‐guardian‐in‐massachusetts/

404 page not found

7 AGE is successor to the former Executive Office of Elder Affairs (“EOEA”), which was renamed in 2024. Like EOEA, AGE is organized under the Executive Office of Health and Human Services (“EOHHS”), and it operates the Adult Protective Services (“APS”) program through the Aging Services Access Points throughout Massachusetts. APS funds only 170 guardianships statewide.

8 Alvarez, Sophia M., J.D., M.S., NCG, Director, Colorado Office of Public Guardianship, et al., 2022 Final Report to the Colorado Legislature (2022). In presenting its findings to the Colorado Legislature in 2022, the Colorado Office of Public Guardianship estimated the numbers of at-risk, unrepresented persons in their state using the methodology applied by Moye, et al., in a 2016 study commissioned by the Institute. (See Note 6, supra.)

A. DEFINING PUBLIC GUARDIANSHIP9

The term, “Public Guardian” refers broadly to a variety of programs that are created, funded and operated in different ways in various jurisdictions around the U.S. They share a purpose to help the most indigent and vulnerable persons with decisional needs, but otherwise they vary considerably. We are aware of four general models.

1. Government as Guardian.

2. Privatized Public Guardian.

3. Private Appointment Originated by a Public Agency.

Privatized guardianship also takes the form of state agencies contracting directly with private individuals, often in concert with some certification process, to serve as guardians for members who fall within their respective service mandates. Washington State has established a Certified Professional Guardianship and Conservatorship Office that sets criteria and standards for individuals interested in being appointed a guardian, who then apply to be matched with unrepresented at‐risk individuals through the state’s Office of Public Guardian (“OPG”). Contractors are paid $750/month ($9,000/year annualized) for the first three months, and $525 per month thereafter, plus $1,800 every three years for legal expenses.

Kansas Guardianship Program is a volunteer‐based variant of the private‐appointment model. Volunteers are recruited and trained, but not paid. Some financial support is provided to cover out‐of‐pocket expenses. The program also supports volunteers with supervision when requested, and events throughout the year to establish its presence as a guide and mentor.

Two agencies in Massachusetts, DDS and DMH, provide guardians under the private appointment model, paying them more than the volunteers receive in Kansas, but much less than Certified Professional Guardians are paid in Washington. DDS pays about 1,000 guardians an average of $100/month to spend two hours per month supporting an individual. DMH pays about the same for a much smaller number of individuals (less than 50 in 2016).

The rates that DDS and DMH pay are approximately one tenth of the cost per case of the appointments funded by APS in Massachusetts.

4. Privately Funded Public Guardian.

9 Decisions made by court‐appointed fiduciaries may concern either the “person,” meaning medical, social, educational, travel, appearance and similar personal choices for the individual; or the “estate,” meaning the income, assets and other financial interests of the person. States vary somewhat in the terms they use to identify these two categories. Most distinguish between “guardian of the person” and :guardian of the estate.” A few use the term, “conservator of the person” and “conservator of the estate.” Still others, including Massachusetts, deem decisions about the person to be the exclusive domain of a “guardian,” and decisions about the estate to be the exclusive province of a “conservator.” This Report uses the term, “guardian,” to refer to both guardians and conservators, unless the context clearly limits its meaning to guardianship only.

10 See Office of the Cook County Public Guardian Website, profile of the Public Guardian, Charles P. Golbert, Esq. Interestingly, Mr. Golbert is named individually as the fiduciary in all adult guardianships and conservatorships handled by the Office, assisted by scores of individual case managers and related program staff.

11 Not insignificantly, interest income from assets managed under conservatorship is used to fund a portion of the whole agency budget.

12 California uses the term “conservator” for appointments over both the person and the estate. In the context of this comparison of state programs, we will call them “guardians,” in order to use consistent terminology.

13 Cost issues will be discussed, infra, but it should be noted that these financial figures suggest a cost of about $10,000 per year for each funded guardianship. This figures is strikingly similar to the amounts paid by the Protective Services Program (“APS”) in Massachusetts to its four guardianship vendors. But the scale is complete different. Dade County funds literally ten times as many guardianships as the Massachusetts APS.

14 More information is provided about PGS in Section E.2 of this Report.

B. THE CASE FOR PUBLIC GUARDIANSHIP

1. Reward for Doing the Right Thing.

The growing interest in a Public Guardian for Massachusetts is not just a response to the needs of the unrepresented, at‐risk individuals in our communities, although it certainly is that. It also is a call for rational public policy, for society’s sake. In order to illustrate this, we offer first an example of the difference that guardianship can make for an individual when the guardian invests the time, patience, training and commitment to connect with and support that person. The example we offer is the experience of Richard D., who had been chronically homeless for much of his adult life.

Richard is a 56‐year‐old man who had been homeless for an unknown number of years when PGS was appointed as his guardian, in June of 2021. He suffers from severe schizophrenia, for which he had been hospitalized scores of times, for varying lengths of time, throughout his adult life. PGS was appointed as guardian during a hospitalization, but thereafter he was unreachable except when hospitalized, which was every few weeks. His designated Care Manager, MF, used these opportunities to meet with Richard, talk with him and build trust. This went on for the better part of three years, while MF and Richard’s DMH case manager tried unsuccessfully to coax him off the streets. The work began to pay off, finally, when In March, 2024, Richard took up residence in a rooming house in Quincy. A month later, however, he was diagnosed with cancer. His doctors immediately wanted to admit him to a nursing home for care during cancer treatments; Richard, true to form, refused. MF knew him well enough to support his decision, even though she did not necessarily agree with it. Richard has stayed in the boarding house for more than a year at this point. Most significantly, he also has been going to medical appointments with MF and accepting antipsychotic medication. He has been hospitalized just once in the past year, and this was for cancer treatment, not psychiatric symptoms.

This case shows the kind of difference in the individual’s life that the right kind of guardianship can make. Stabilizing Richard with appropriate services has improved his quality of life significantly. But there are financial and social gains as well. Our health care system was paying thousands of dollars each month, through the free‐care fund, homeless shelters, and emergency services that were sent to bring Richard to the hospital when, instead of bringing himself in (which he regularly did), he was found wandering on busy streets without adequate clothing. Studies in Connecticut and New York over the last eight years have documented that the cost of the kind of guardianship that Richard has been offered is more than offset—several times over—by savings in the cost of emergency medical care, incarceration, civil and criminal court costs, shelters and security services that are reduced or prevented.

2. Economics of Guardianship: What Are We Waiting For?

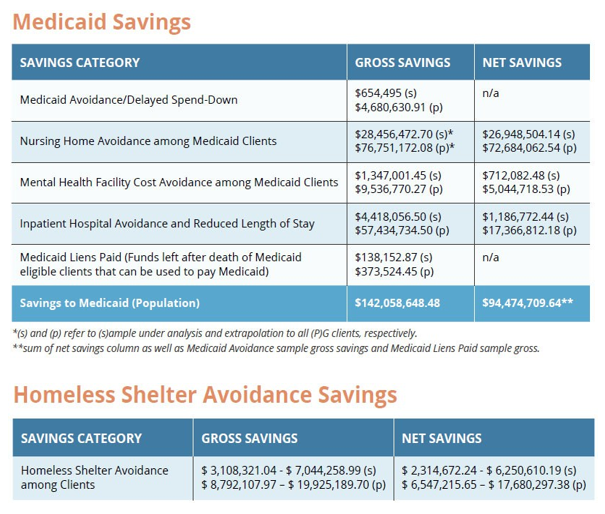

The extent of immediate financial benefits that the state accrues by supporting its at‐risk population is more than a little surprising. There have been two seminal reports, one from a program in Connecticut in 2019 (the “GAL Study”) and one from New York City in 2024 (the “Project Guardianship” study), that both show tremendous cost savings when guardians can stabilize a person who otherwise would be in and out of hospitals, shelters and/or jails. The GAL study compares before‐and‐after annual public expenditures for 217 participants in a “wrap‐around”15 guardianship program in Connecticut.16 The Project Guardianship study was longer (nine and a half years), but involved a smaller sample 86, vs. 217 in Connecticut.

The numbers from these reports strain credulity, but appear to be reliable. We cross referenced the reduction of hospital days that were avoided against the dollar amount of savings that are reported. The numbers match up. For example, the Connecticut study shows that the average number of days of hospitalization declined by 23 days per participant. The cost of a psychiatric hospitalization in that state is $3700/day. Based on this rate, savings in hospital costs alone account for $84,572 per person per year, out of a total of $85,808 per person per year for all categories of public expenditure.

Outcome

Estimate cost per incident

Conservative estimate

First-year change per client

Total first-year change (N=217)

Psych. hospitalizations

$3715 per daya

–$84,572

–$18,352,100

Emergency room visits

$1482 per visitb

–$581

–$125,970

Days incarcerated

$170 per dayc

–$656

–$142,290

Total

–$85,808

–$18,620,360

Project Guardianship in New York City shows comparably eye‐popping savings from a comprehensive guardianship program. The combined reductions in state expenditures for hospitalizations, nursing home admission, psychiatric hospitalizations and shelter costs averaged $67,000 per year per client:

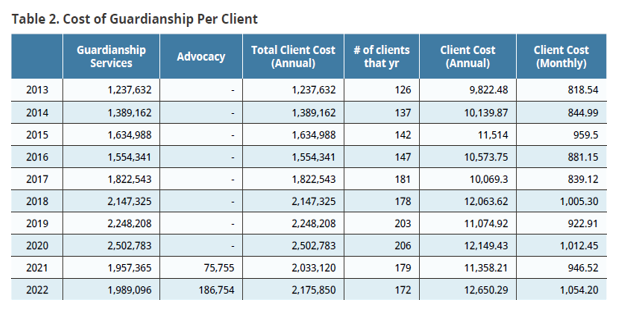

The monthly costs to operate the program ranged from $818.54 ($9,822.48/year) to $1,054.20 ($12,650/year) for each client. These costs were factored in to the savings reported by Project Guardianship ($67,000 per year per client). Please note the following chart of calculations:

The Institute is not a finance or budget office, but the numbers reported in these two studies do not seem to require an expert to interpret. If Massachusetts accrued savings of

$70,000 per year in its Medicaid expenditures for one‐third of the unrepresented, at‐risk individuals considered in this report, it would add $70 Million to its revenue each year.17

3. Reality of an Underfunded Guardianship System.

The outcomes described above—both the clinical changes in Richard’s life and the unexpected financial advantages of the GAL Program and Project Guardianship—contrast starkly with the grim reality of the financially neglected, almost accidental guardianship system that has evolved in Massachusetts. A much more limited level of involvement is offered to the vast majority of unrepresented and at‐risk individuals. The Probate Court in Massachusetts—like that of many other jurisdictions—for the past 40 years has relied upon a volunteer/pro bono model in proceedings involving unrepresented, at‐risk individuals. The persons agreeing to take these appointments typically are able to set aside 25 hours or less per year to perform the duties of the guardian. Generally they are paid, if at all, less than $1,500 per year for each appointment.

Due to poor compensation, the volunteer/pro bono model often, but not always, results in low commitment to the appointment, but not necessarily because of the guardian’s preferences. Such assignments are made in crisis, where the individual for whom a guardian is sought has no income or assets (or is not well‐enough known to determine this), there is no known family member or friend capable of stepping in, and the petitioner is a third party with a job to do, which it cannot do until a guardian or conservator with legal authority has been appointed. The petitioner is not necessarily insensitive to the circumstances of the individual, but its interest is to procure legal authority to take appropriate, urgent action. For example, a hospital needs to transfer someone who no longer needs acute care to a subacute facility; a pro bono attorney is trying to stop an eviction; an agency needs to qualify the individual for Medicaid; or some other third party in some other situation is trying to protect the individual from injury or loss.

The Court in this situation has no resources to find to find a professional willing to take the appointment. Private attorney petitioners report that often they have no one to nominate as guardian, and that the Judges now are putting the burden on them to find someone, or the petition will not go forward. Probate Court judges are increasingly calling for more resources to be committed to funding for guardians.

Concerns about this process do not end if or when a volunteer is found. The duties of a guardian are described in statute, G.L. c. 190B, §5-301 to 313, but in most cases it is not a secret that the guardian will do his or her best under a volunteer/pro bono standard of care. In that role, there may be up to three sources of minimal compensation for the guardian, which, as noted, will average $1,500 per year ($125 per month) combined. These are (1) payment from a state agency, if the unrepresented person is a member; (2) payment from the Probate Court under the “Rogers”18case, if the individual requires antipsychotic medication; and/or (3) payment of fees allowed by the MassHealth program from the income of an individual (assuming they have such income) while receiving skilled nursing home care paid by MassHealth (known as “Rudow” fees19).

In some cases, the guardian can collect both Rogers and Rudow fees. But both the Probate Court and MassHealth must approve fees allowed under Rudow before they can be paid. The time, effort and tolerance for delay in receiving both Rogers and Rudow fees is such that many professional guardians forego them.

Volunteer guardians frequently do outstanding, caring work, putting in far more time than they are paid for. But many cannot do so, because they have families and careers. Many of the most reliable have retired recently. If the goal of guardianship for an unrepresented individual is long‐term stabilization in the least‐restrictive setting that can meet their needs, few are getting there.

Shortages of community resources for long‐term placement is a big part of the problem. Housing and community‐based care can be obtained, as demonstrated by Richard’s experience in the example above, if the guardian stays with the individual for long enough. But few unpaid professional can stay with the case for long enough. The guardian changes, or goes unreplaced. Far too often in these situaions the individual continues, or begins once again, to cycle through short‐term or failed placements and repeated transitions in care. Forced transitions from unstable placements are the “cracks” in the safety net through which the unrepresented fall.

The cost of inaction in the face of this crisis goes beyond financial, and even beyond individual suffering. We incur losses in the appearance of our community, even in our civic pride, when we leave significant numbers of vulnerable people to fend for themselves on the street. The cost of providing a Public Guardian is, by comparison, a tremendous bargain.

4. Duties of the Public Guardian.

The PGS employee who worked with Richard in the previous example, MF, is a licensed social worker; the level of service she provided contrasts with the limited help that is possible under the volunteer/pro bono model described above. MF exemplifies what can be called the “social‐work” model of guardianship. Most jurisdictions would describe it simply as a “professional” model. Individuals with decisional impairment who have money can obtain professional‐level services from many sources. But until Massachusetts has a Public Guardian, almost no indigent person with the same level of need has this option.

A guardian who is able to provide a social‐work level of care often will commit 100 hours or more per year for each appointment. He or she will oversee a full range of medical, behavioral, social and physical services that individuals with significant decisional disabilities typically require, whether living in the community or in a facility. The Public Guardian addresses this responsibility in several ways, by:

I. Establishing requirements or credentials to certify individuals who are qualified to be guardian, if he or she has no prior relationship with that individual.

II. Establishing standards of care for certified guardians, including assessment of needs and resources available to the individual, and learning the range of decisions that may need to be made. Below is a sample listing of what may be assessed:

a. Living Situation and Environment

- Safety, access, habitability, lease status

- Appropriate independence: preferences and physical capacities for independent living, group home, rest home, assisted living, skilled nursing

- Access to public or subsidized housing

- Concerns about abuse, of or by others

b. Health Care and Medical Needs

- Capacity to make or participate in decisions

- Consent to treatment for which individual cannot consent

- Chronic conditions and access to medication

- End‐of‐life planning

c. Needs for Supervision or Help With Personal Care

- ADLs (bathing, dressing, eating, ambulating)

- Specific therapies (speech, physical therapy, occupational therapy, etc. )

- Instrumental Activities of Daily living (IDLs) – need for home care services for cleaning, and other home maintenance tasks

d. Finances

- Management of assets (investments, savings, real estate)

- Knowledge and monitoring of sources of income

- Paying bills, taxes, other financial obligations

- Review of insurance policies

- Investigation of any evidence of financial exploitation

e. Public and Private Benefits Programs

- Social Security (retirement, SSDI or SSI)

- Need for a Representative Payee

- Medicaid (including PACE, SCO, & community based waivers

- Medicare

- DDS or DMH services

f. Other needs and services

- Recreational and social activities

- Education or employment

- Transportation

- Companionship and support

III. Responding to and updating assessments as needed, by ensuring that appropriate actions are taken for the individual

a. Completing and submitting applications for benefits, including appeals of denials

b. Making referrals for appropriate medical or psychiatric care

c. Advocating for the individual

- Legal rights

- Relationships

- Goals and wishes

- Ensuring use of least restrictive alternatives

d. Interacting with other professionals to stabilize or improve the individual’s circumstances

- Healthcare providers

- Social workers

- Lawyers

IV. Building and maintaining a relationship with the individual and whatever residential community the person is living in

Guardianships that conform to the above sample list of responsibilities are financially out of reach for indigent, at‐risk individuals. The only publicly-funded tial access that the unrepresented person may have in Massachusetts today is through APS. APS investigates reported abuse, and if it finds a situation that rises to its high standard of risk, and if there is no other way to protect the individual, APS pays a non‐profit agency provider about $10,000 per year to serve as guardian. As noted, however, APS funds only 170 appointments statewide, against the estimated need for 3,000 to 4,000 appointments.20

5. Scope of the Guardianship Crisis.

Homelessness is only one of many significant causes of decisional risk to unrepresented individuals. Another major concern is the continued use of skilled nursing facilities to house individuals who, in an earlier time, would have been institutionalized. The professional‐level, social‐work work model of guardianship is, in most cases, the best hope that an unrepresented individual may have for escaping such de‐facto incarceration. Jason’s case is another good example:

Jason is a 66‐year‐old man for whom PGS was appointed guardian in September, 2021, who suffers from cognitive degeneration, alcoholism and mood swings that render him unable to care for himself. It was believed that he could thrive in a group home, but efforts to arrange that were thwarted by a low‐level sex‐ offender claim on Jason’s record. Over a period of three years, his PGS care manager, MF, built a relationship with Jason, kept him in touch with his estranged family, and had his legal issue reviewed by criminal counsel. MF also looked persistently for a less‐restrictive group home placement that would accept Jason’s history. In April, 2025, he was discharged from the nursing home, to take up residence in a group home, where he is experiencing a much freer life, which also is significantly closer to the sister with whom he still has a good relationship.

An outcome like Jason’s simply is not possible without the care and persistence of a guardian performing at the standard of care that MF has provided. This is a tremendously important reason for establishing a Public Guardian in Massachusetts.

6. Hidden Crisis: The Need for Thought Leadership in Guardianship.

Massachusetts does not lack caring, committed and experienced advocates for the most vulnerable, including those who serve as guardians and many who direct agencies that do this work. Others teach and do research, not just in guardianship law or practice but on the disabilities that are associated with this area of need. We have internationally- recognized experts on these most difficult issues all over the state.

What is missing, and has been missing for 40 years, is institutional leadership to help all of those who champion the cause to pull their oars in the same direction. In addition to consistent institutional support, we need planning and anticipation of the effects of changes that may improve the system. A major purposes of a Public Guardian, in other words, is to break the cycle of reaction to crisis. We need to anticipate as well as react.

But making the right move in guardianship law is, in fact, harder than for many other policy endeavors. Massachusetts has a history of resistance to reform of guardianship law.21 The Institute proposes that, for this reason, and because guardianship so often is complex and conflicted, it needs the steady hand of stable, informed and committed public office to provide direction. An historical example helps to show what we mean.

a. Unintended Consequences

The guardianship statute in Massachusetts came under scrutiny in the mid-1980’s from advocates in the disabilities rights movement, who increasingly were concerned about a lack of due process in guardianship proceedings for the most vulnerable respondents. Like most states (both then and now), Massachusetts protects the rights of individuals by extinguishing their own legal efficacy, to the extent of the interests that are meant to be protected.22 Legal capacity under this regime was and remains a zero-sum concept, if carefully parsed to identify specific functions. Its scope may be narrowed, but within those bounds, its legal effect is the same.23

Due process undercuts this way of thinking about guardianship, and reveals the extent to which the doctrine of parens patriae—which assumes that the person taking charge was king before he was guardian, and would remain king thereafter—still tilts the game in favor of the petitioner. By insisting that the respondent be heard, due process aims toward something more capable of nuance, and more able to consider the individual’s own views and preferences.

The urgency of due process was fueled by troubling cases in which guardianship and conservatorship were being used to do real harm (e.g., an elder removed from her home and placed involuntarily in a nursing home under color of law). Bills were filed, beginning in 1987, and again in every legislative session for two decades, that would give vulnerable respondents better notice, stronger rights to legal counsel, more court oversight, and other procedural protections.

This was an epic struggle that went up against a history of inaction on guardianship law in in Massachusetts,24 and it took literally 22 years and more than twelve separate filings of proposed legislation for this advocacy to bear fruit. In 2009, following an investigation and report by the Boston Globe Spotlight Team, the MUPC finally was enacted.

The MUPC was big step in the right direction. But, as described above, Massachusetts has relied for 40 years on a system that lays pro bono expectations (and yes, demands) upon probate attorneys, social workers and clinical consultants to accept appointments for unrepresented individuals who will never be able to compensate them. The MUPC did not rectify, or even acknowledge this history. Instead, it added procedural requirements and due process protections, as intended, which have driven up the cost to these volunteers to serve in a pro bono capacity, to the point that there aren’t enough volunteers anymore–which was not intended. The shortage of qualified pro bono guardians was acute when the Institute was established in 2014, five years after the MUPC was passed. Today, eleven years later, the problem is worse.

The concern we are raising in this example obviously is not that the MUPC shouldn’t have been passed. The point is that guardianship reform needs a steady hand, not confrontations in the media. It is difficult for advocates who propose changes in one part of the guardianship system to know about, let alone predict, the way that their proposals will affect others in different parts of the system. The surprise delivered by the MUPC is a painful example of this principle.

b. More Unintended Consequences?

A very similar potential problem of unintended consequences is brewing at the present time, as a result of legislation that is supported by the health care system and the Probate and Family Court in Massachusetts, that is meant to provide a new source of professional guardians for the indigent. This legislation would create a program to recruit and support, with training and guidance, a corps of retired attorneys, health care professionals, social workers and others who would be paid a stipend for appointments as guardian for unrepresented at‐risk individuals. A compelling reason for this proposal is the current crisis in the state’s hospitals, where an estimated 2,000 beds each day are occupied by patients who are ready for discharge, but who lack decisional capacity to agree to transition to sub‐acute care, or who have nowhere to go.

The intentions and rationale for this proposal are beyond reproach. But it does not take a fortune‐teller to predict that the guardianships that may result from this effort, if it comes to fruition, are likely to be unstable and short‐term. Every case where a retiree needs to step down will require a petition to resign and a petition to replace the guardian. Replace with whom?

Another short-term appointee? Does the Probate Court have the capacity for this new case load, including the turnover rate, which could be substantial?

The Institute is not in the habit of discouraging well‐intentioned ideas. But unless the bill includes a $20 Million annual budget to pay the true cost of appropriate guardianship for 2,000 new appointments, both now and for the lifetimes of the individuals being served, its unintended consequences may, in the long term, do the kind of harm that the much‐valued MUPC has set in motion for the vulnerable, unrepresented individuals who, as a result, need a Public Guardian now more than ever. The rational approach to alleviating the crisis in guardianship is to spend $20 Million dollars on a Public Guardian, rather than for yet another program that would interact in unknown ways with other parts of the system.

A history of poorly-coordinated action is perhaps the single most compelling reason to establish a Public Guardian for Massachusetts. There has to be a place in government where qualified public administrators can consider the needs of unrepresented, at‐risk individuals from an appropriately long‐term perspective, and where they will bring to this task the skills and the institutional support to identify a funding stream that is commensurate with the tremendous good, both financial and moral, that a Public Guardian can do for Massachusetts.

14 More information is provided about PGS in Section E.2 of this Report.

15 “Wrap‐around” implies a very intensive level of intervention by a guardianship team, which checks in weekly, has frequent in‐person visits, maintains updated care plans and provides social and therapeutic support to participants. It generally provides a higher level of support than the social‐work model discussed in this Report, but in some circumstances, such as for a person living in a group home, the levels of care may be comparable.

16 See Levine, E., et al., Outcomes of a Care Coordination Guardianship Intervention for Adults with Severe Mental Illness: An Interrupted Time Series Analysis, Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, Vol:.(1234567890) (2020) 47:468–474 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488‐019‐01005‐11 3.

17 Since about half of all Medicaid expenditures are reimbursed by the federal government, it would be entitled to claim half of the projected savings. Massachusetts thus would keep “only” $37.5 Million in savings.

18 The name comes from the case in which the requirements and processes for these medications first were delineated. See Rogers v. Commissioner of Department of Mental Health, 390 Mass. 489 (1983).

19 This refers to Katherine Rudow v. Commissioner of The Division of Medical Assistance, 429 Mass. 218 (1998), in which MassHealth was directed to allow an individual who consent to medical care, and requires a guardian for that purpose, to allow that individual to deduct a deemed maximum “reasonable” guardianship fee from the income that the person otherwise must pay to the facility.

20 The non‐profits who take these cases are able, through various funding streams, to accept another 100‐2000 appointments, for which they provide the same social‐work level of professional guardianship as they provide for APS cases. But these tend to be “light‐duty” appointments, because they do not bring in any new revenue, and the agencies are audited to restrict the use of APS funding to cover costs of non‐APS referrals.

21 Until 2009, the title of our guardianship statute—“Guardianship of the Insane and Spendthrifts”—was embarrassingly antiquated. Such demeaning terminology had long been jettisoned in most states, based on new depths of understanding of the causes of decisional incapacity, including severe mental illness, intellectual disabilities, brain injury, stroke and most other medical events. Indeed, the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA) was enacted in 1990, twenty years before Massachusetts renamed its guardianship statute. We can only speculate as to why this area of law is so resistant to change in Massachusetts. One possibility is that it suffers from its close association with medicine, which is notoriously slow to change fundamental concepts.

22 The legal standard for a court to carry out this law is whether the individual has “capacity.” This was a better standard that the ideas of “competence” that had been inherited from the 19th century, but it did not move any great distance away from parens patriae as justification for guardianship. See Glen, Hon. Kristin Booth, Ret., Changing Paradigms: Mental capacity, Legal Capacity, Guardianship, and Beyond, 44:93 Columbia Human Rights Law Review, Vol. 1, p. 98 (Fall, 2012). Judge Glen was a judge for 30 years in New York, serving on the New York City Civil Court of New York County from 1981 to 199, the York County Supreme Court 1986 to 1993, as an associate justice on the 1st Judicial District (New York) Appellate Term from 1993 to 1995, and the New York County Surrogate’s Court from 2006 until 2012. She currently is a member of the American Bar Association Disability Rights Commission.

23 In the 19th century, Massachusetts law had shifted to medicalized terminology, but the definitions of illness themselves remained vulgar from a modern perspective. The Massachusetts Revised Laws of 1902, for example describes persons subject to guardianship as “insane,” “imbeciles” and “idiots”. See Massachusetts Revised Statutes, Chapter 145, pp.1307‐1314 (1902). In most other jurisdictions, those terms had been replaced by terms like “incompetent,” or “incapacitated” decades before. In addition, as late as 2009, “mentally retarded” and “of advanced age” were statutory grounds for imposing guardianship.

24 See Note 17, supra.

C. MODELS OF PUBLIC GUARDIANSHIP

The Institute is committing to advancing best practices in guardianship, both through its members, and in this Report. The theme that we emphasize is “person‐centered” guardianship. There is a long history to this term, which need not be recited here. As we understand it, a person-centered approach requires that a guardian (1) spend time with the person and get to know their needs and wants; (2) if appropriate, use planning tools to identify preferences and choices; (3) encourage autonomy and self‐advocacy; (4) offer support when asked or needed, but collaborate rather than act in place of the person; and (5) continuously evaluate the quality of the relationship and seek supervision or peer‐group support as guardian.

These principles are useful because they are general. In order to be more specific, we have chosen two perspectives from which to describe guardianship. These perspective overlap, but they bring out different qualities of a guardian’s involvement in the life of an individual. They consist of (1) roles and (2) clinical circumstances.

Our sources for the views we express here are based upon the experience of Institute members with PGS; the work of member organization Center for Guardianship Excellence; participation in conferences of the National Guardianship Association (of which member Heather L. Connors, Ph.D., was president in 2022‐23); information learned from the Colloquia and Conferences that the Institute sponsored from 2015 through 2019; and meetings of the Institute over its 10‐year existence.

1. Roles of a Guardian.

Decision‐maker. Under current Massachusetts law, the purpose of guardianship is to make decisions for individuals deemed unable to act in their own best interests. This authority is granted on the basis of findings of functional incapacity:

A guardian shall exercise authority only as necessitated by the incapacitated person’s mental and adaptive limitations, and, to the extent possible, shall encourage the incapacitated person to participate in decisions, to act on his own behalf, and to develop or regain the capacity to manage personal affairs. A guardian, to the extent known, shall consider the expressed desires and personal values of the incapacitated person when making decisions, and shall otherwise act in the incapacitated person’s best interest and exercise reasonable care, diligence, and prudence.25

This was a significant revision of law prior to the MUPC, and considerable effort has gone into encouraging limited, as opposed to plenary, appointments in Massachusetts in response to the new standards. The statute statess this intention expressly, after the general grant of authority, above: “A guardian shall immediately notify the court if the incapacitated person’s condition has changed so that he or she is capable of exercising rights previously limited.”26 We are not aware of any research on the success of the effort to favor limited over plenary guardianship. Anecdotal information suggests, however, that the effort generally has not been successful.

Also apparent in the above language is the distinction between the traditional “best interests” standard and the “substituted judgment” standard first articulated by the New Jersey Supreme Court in 1976,27 which was adopted in Massachusetts case law in 1977, just a year after the Quinlan decision,28 and then incorporated into the Uniform Probate Code in 1997.29 The Institute’s interpretation of this guidance is that substituted judgment should be used whenever possible, but if the individual’s likely choice cannot reasonably be known, the guardian should choose in the best interests of the person.

Massachusetts law includes express limits on a guardian’s (but not the court‘s) use of substituted judgment in select circumstances. Guardians do not have authority to consent to antipsychotic medication, to revoke a health care proxy, or admit to a mental hospital, DDS facility or nursing home without a court order that has been obtained by petition. A more general rule is that guardians cannot make “extraordinary” medical or financial decisions, including estate planning, without such an order. Massachusetts case law authorizes a guardian to consent to do‐not‐resuscitate (“DNR”) medical orders if the individual’s substituted judgment is well‐known and not disputed, but some sources interpret this obscure section of the law to require a court order in all cases.30

Advocate. In practice, the role of guardian may go beyond decision‐making, if the guardian becomes aware that the well‐being of the individual would be enhanced, or unwanted consequences could be avoided, by advocating for the person in any of a wide variety of circumstances. This could include eligibility for public benefits; membership in DDS or DMH; services of a vendor; acceptance into a venue or an organization; employment or education; procurement of housing from public or private landlords. There is no defined list for when, where or how a guardian may support the individual through personal advocacy.

The role of advocate may include hiring a lawyer or other third party to advocate or represent the individual in a forum or circumstance.

Quasi Social Worker. Many guardians are licensed social workers, which may both simplify and complicate their work as a guardian. Clinical familiarity with mental illness or developmental disability may give a licensed social worker insight into the significance of behaviors, or an ability to communicate with the person, as well as knowledge of treatment modalities, ideas for services that may improve the individual’s life experience, or realistic expectations of his or her capabilities.

The tasks described above can be strikingly similar to the assessment and service coordination roles that social workers perform in many places of employment. For this and other reasons, social workers can be very good guardians for individuals who require many services. Guardianship can look and feel like social work.

In rare instances, the obligations of a social worker might come into conflict with his or her role as guardian. For example, as a mandated reporter of suspected abuse,31 a social worker who observes the individual abusing a child, the guardian may be faced with a dilemma. If the visit, as guardian, is considered to be in a ”professional capacity,” the legal and ethical duties to report the individual would be triggered; but would the filing of a report be a violation of the guardian’s fiduciary duty to the abuser? We are not aware of any current court cases or administrative rulings addressing this question.

Friend. The experience of guardians not infrequently is that they feel and act like friends of the individual for whom they have been appointed. The amount of time spent with that individual may be a factor in how both parties view the relationship.

A guardian is not relieved, however, of any fiduciary responsibilities by virtue of establishing friendship with the individual. Friendship is a two‐way relationship; guardianship is not. If friendship is of value to the individual—as it is likely to be for many unrepresented individuals—then providing it may be within the role of guardian. But the benefit must be for the individual and not the guardian. Self‐interest must be a boundary that the guardian does not cross.

2. Circumstances of Guardianship: Determinants of Decisional Impairment.

The reason for an individual’s decisional impairment may have a strong impact on how guardians will conduct themselves. The interface of the skills of the guardian and the condition of the individual is what is meant by the “circumstance,” which we organize in terms of the condition that is associated with the guardianship. We identify summarily six such impactful conditions:

(i) Dementia

(ii) Brain injury

(iii) Blindness/deafness

(iv) Mental illness

(v) Intellectual/developmental disability

(vi) Genetic conditions (MS, ALS, Hodgkin’s disease)

These conditions will influence a guardian’s work. A purely random listing of such factors may include: what kind of residence the individual lives in; how much time he or she is comfortable spending with the guardian; what kinds of subjects can be discussed; whether the individual is ambulatory and/or interested in going places; whether the guardian’s personal safety is a potential concern; whether the person’s illness dictates time of day for visits; what the individual will remember or learn from interactions; what kind of family may be involved, and in what capacity; and so on.

The conditions surrounding the appointment may be more important, in some circumstances, than trying to identify or describe a guardian’s role in abstraction. The same role in different circumstances may look very different and make different demands upon the guardian.

25 Massachusetts General Laws, c. 190B, §5‐309(a) (2025).

26 Id.

27 See In re Quinlan, 70 N.J. 10, 41‐42 (1976).

28 See Superintendent of Belchertown State School v. Saikewicz, 373 Mass. 728, 747‐53 (1977).

29 See Uniform. Guardianship & Protective Proceedings Act § 314 Comment. (1997).

30 See generally Macy, P., A Guardian’s Authority to Consent to DNR/DNI Orders in Massachusetts, Mass. Law Review, Vol. 102, No. 4 (August, 2021).

31 See G.L. c. 119, §51A (2025).

D. THE FUTURE OF GUARDIANSHIP

We are aware of two trends—one local and historical, the other international and focused on the future—in which it seems that a Public Guardian might be able effectively to guide policy, but it is difficult to predict how. The historical trend is the tendency for different groups of stakeholders in guardianship policy to focus on separate passions, which may come at the expense of cross‐group cooperation, if not held in check. For example, elders at risk have the attention of grassroots organizations and national advocates who tend to accept a medicalized view of guardianship, because the people for whom they advocate come to the process primarily as a result of dementias and other progressive diseases that are clearly medical in nature.

Disability rights groups and advocates, on the other hand, can have a completely different perspective, based upon the long struggle against entrenched views by society that a diagnosis of intellectual delay may justify guardianship, and the sense that even a shift to functional standards of capacity misses the point for them. Advocates who are intensely focused on freeing their members to learn, grow and experience the dignity of risk tend not to recognize common purpose with the aims of other advocates who deal with loss of a very different kind, at the other end of the age spectrum; and vice versa.

The other trend is the evolution of society’s expectations and justifications for guardianship, which, as noted above, have come a long way over the past 150 years, and may be headed for even greater change in the next generation. Retired New York Judge Kristin Glen authored a thoroughly researched and well-written review of the story of these ideas in 2012 for the Columbia Human Rights Law Review.32 She writes that, by the early 20th century, rapid expansion of ideas and methods in psychiatry had fixed the understanding of decisional impairment in terms of “competence,” and viewed this condition as a status derived from a medical diagnoses. This medicalized view was upended in the second half of the 20th century, as a result of new scientific, legal and social views of decisional impairment:

[Since the mid‐1960’s] we have observed . . . a paradigm shift. The idea of incapacity as an illness or defect that renders the person suffering it to an object of charity and protection, subject to plenary guardianship based on best interests which constrains her personal life and the control of her property has been re‐examined and largely rejected. This is the “old” paradigm.

With changes in medical practice, psychology, and a burgeoning legal framework of civil rights and procedural due process, we have moved to a functional, cognitive understanding of incapacity. This current paradigm leads to “tailored” or limited guardianships, which represent the least restrictive means of protection, the promotion of greater autonomy for the incapacitated person, and robust procedural protections in the determination of incapacity and appointment of a guardian.33

The ascendance of functional incapacity as justification for guardianship has not dethroned parens patriae as the operative image in law and practice.34 As noted earlier, guardianship in Massachusetts remains zero‐sum in most respects, where authority granted to a guardian necessarily removes it from the individual.

But the ancient rule of parens patriae may, in fact, be changing. To continue Judge Glen’s summation and analysis:

Now, less than two decades later, in an increasingly globalized world, a new paradigm is emerging, premised on international human rights. [Footnote omitted.] This paradigm sees incapacity as socially constructed, insists on the full legal capacity of every person with intellectual disabilities, and does away with substituted decision‐making in favor of society’s obligation to provide appropriate supports to permit everyone to make his or her own decisions. Like every emerging paradigm, this challenges our perceptions and our understanding of when, how, and even if the state may intervene in a person’s life, and it has the potential to be deeply unsettling. And, unsurprisingly, it takes time.35

The paradigm that Judge Glen is referring to is characterized as a “social model” of disability by one of its leading proponents, Professor Ann Kanter, founder and former Director of the Disability Law and Policy Program at Syracuse University College of Law:

The social model places the responsibility squarely on society (and not on the individual with a disability) to remove the physical and attitudinal barriers that “disable” people with various impairments and prevent them from exercising their rights and fully integrating into society. In other words, a person’s impairment does not diminish the right of that person to exert choice and control about his or her life or to fully participate and contribute to communities through full integration in the economic, political, social, cultural, and educational mainstream of society. By relying on the social model of disability, it is impossible to say that any person is “unable” or “unqualified” to exercise rights or to participate fully in society (emphasis added). [Footnote omitted.]36

These are very big ideas, with potential to dismantle guardianship law as we know it. The Institute’s experience through PGS has contributed to a view of guardianship that seems to fall under the “social model” of disability that she has articulated. We use a very similar term, in fact—the “social‐work model”—to describe the type of guardianship that we see as critically important to a successful Public Guardian, as envisioned in this Report.

The value of a person‐centered approach to guardianship does not hinge on a radical rethinking of disability. But the scope of the crisis in guardianship in Massachusetts, considering its time of onset, the numbers of individuals at risk and its persistence over several decades,37 may suggest that social models of disability of the kind advocated by Dr. Kanter should be considered. It seems irrefutable that the consequences of poor judgment, poverty, intellectual disability, mental illness, neurological conditions and other conditions associated with being at risk in society would lead to less crisis and dependency if safe housing options and robust community services were not difficult to get.

The implication is that, as Dr. Kanter argues, if society provides the resources, it may not find that so many citizens are “disabled,” and it won’t need so many guardians or conservators to see to their needs. These are new thoughts about guardianship, and they will offer more possibilities for state policy in the future if approached with clear purpose, good data, and consistent leadership.

32 See Glen, supra,, Changing Paradigms: Mental capacity, Legal Capacity, Guardianship, and Beyond, at p. 98.

33 See id.

34 There is a broad consensus, for example, that the use of limited guardianship in Massachusetts has not increased significantly since the MUPC was enacted, nor has restoration of rights become more common.

35 See Glen, supra .

36 See Kanter, Arlene S., The Globalization of Disability Rights Law, 30 Syracuse J. Int1 L. & Com. 241 (2003).

37 The guardianship crisis in Massachusetts started in the mid‐1980’s, which was roughly in the middle of the state’s process of deinstitutionalization, during which tens of thousands of residents of state mental hospitals and state schools were transitioned into the community over a period of about 20 years (from 1971 to 1995). A connection can be inferred from this coincidence that deinstitutionalization impacted the guardianship system. If, as frequently is asserted, an adequate infrastructure of community housing and services was not provided to support so many new needs, those having the fewest personal or family resources would be the ones ending up in emergency rooms, shelters, jails and public spaces to ask for help. As we have noted throughout this Report, these are channels that have been flooding the guardianship system for four decades. But is this outcome preordained by the frailties of the respondents? Would the outcome change if safe housing were not scarce, or if community services were not in short supply, bureaucratically overburdened and fiscally unstable?

E. HOPEFUL SIGNS

1. Office of Adult Guardianship and Conservatorship Oversight (“OAGCO”)

In 2021, the federal Administration for Community Living38 awarded competitive grants to seven states, including Massachusetts, to support better oversight of guardianship services in those states. Massachusetts received just under $1 Million, which has been used to establish the Office of Adult Guardianship and Conservatorship Oversight (“OAGCO”) over the past four years. OAGCO opened to the public in January, 2025.

OAGCO has tabulated the number of active guardianship and conservatorship cases in Massachusetts, for the first time in the Court’s history. This is an important achievement toward forming a basis for a robust public guardianship system in Massachusetts. The numbers reported are daunting: approximately 29,000 guardianships and approximately 6,740 conservatorships. With about 4,000 new cases filed each year, the demand for guardians and conservators remains high.

2. Public Guardian Services

Public Guardian Services (PGS) is a non‐profit guardianship program that was formed in July, 2019, to carry out the mission of its parent company, Guardian Community Trust, Inc. (“Community Trust”), to foster a practical solution to the decisional needs of unrepresented at‐ risk individuals in Massachusetts. Community Trust itself is a non‐profit trustee that operates both individual and pooled special needs trusts pursuant to the federal Medicaid statute, 42 U.S.C. §1396p(d)(4), and state Medicaid law and regulations promulgated thereunder, solely for the benefit of persons with disability.39

The Institute serves as an informal sponsor of PGS, which is funded by an annual grant from Community Trust. The initial intention of the Institute was not to sponsor a provider of guardianship services, but to propose and advocate for legislation allowing Community Trust to partner with the state to provide both guardianship and better oversight of such appointments for persons who are unrepresented and at risk. For a variety of reasons, this proposed legislation, which was filed for the first time in 2017, did not get far in the Legislature, just as fourteen prior Public Guardianship proposals that had been filed during the previous 30 years did not succeed.

In 2018, Retired Supreme Judicial Court Justice Margot Botsford40 met with the Institute to discuss its public guardianship mission. Her recommendation was to show state leaders exactly what we had in mind, rather than wait for the Legislature to come around before starting a pilot. This was good advice, and we followed it. PGS was established as an LLC in July, 2019. It began operating from offices in Braintree in January, 2020, taking appointments in Suffolk and Plymouth Counties, and adding Norfolk in 2021.

Less than 60 days after PGS opened its doors, the COVID‐19 pandemic hit Massachusetts. The contagion restricted every aspect of guardianship, from the operation of hospitals from whom referrals normally come, to disrupting access to judges and courtrooms as required in order to make appointments, to closing community care facilities and nursing homes where the clients of PGS would reside, to virtually shutting down direct visits with clients. This situation continued from the first quarter of 2020 until mid‐2022, when restrictions finally were lifted.

Despite this unexpected challenge during start-up, within six months PGS had accepted appointment as guardian and/or conservator for 80 unrepresented individuals.41 In addition to supporting directly the unrepresented, at‐risk population whose needs the Institute had been established to reach, we have gained an understanding of the larger institutional context of this mission that we now view as irreplaceable. We hope that the time and commitment that have gone into PGS will help Massachusetts to make the transition from a frustrating and overstressed guardianship system for the poorest and most vulnerable, to a fully‐supported Public Guardian that can assert the kind of leadership in health care policy in this area of practice that the rest of the country has come to expect from Massachusetts.

38 The Administration for Community Living (“ACL”) has been gutted by the administration of former real estate developer, now President, D.T. Trump, as part of a policy to defund government social services. Apparently most ACL staff have been reassigned rather than fired, so there is reason to believe that ACL may be reconstituted as some point in the future.

39 Community Trust is one of four recognized non‐profit organizations that operate pooled trusts in Massachusetts. These programs together serve nearly 2,000 persons with disability throughout the state. Pursuant to the federal authorizing statute, amounts that remain in pooled trust accounts are subject to claim by the Medicaid program after the lifetime of the beneficiary, up to the amount of medical benefits paid during lifetime. In 2024, the four pooled trust programs in Massachusetts together reimbursed nearly $20 Million to the Medicaid program. These amounts represented over 40% of all reimbursement that the state recovered that year.

40 Justice Botsford had been awarded a one‐year Fellowship from the Access to Justice Commission to consult with the Trial Court about its processes, including guardianship practice and procedure.

41 80 was PGS’s maximum case load, with four social workers providing Care Management for 20 individuals each.

F. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

1. Conclusions.

A theme that has emerged from preparing this report is that guardianship can be instituted and implemented along a spectrum of models. The Institute does not pretend to be neutral about whether the social‐work model, as we have identified it and now refer to it, is not just different from low‐commitment guardianship. It’s better. But if that answer is clear, it also begs the question: better than what? We are reminded, as we review ten years of advocacy, that people can and do disagree about what can justify appointing a guardian, and what truly is lost as result. Such disputes are not likely to end anytime soon.

Another theme that is implicit in this review is that the guardianship relationship is a verb more than it is a noun. The concept is defined today by what the guardian does for the individual, much more than the static authority that the guardian wields. This change in expectations may explain why there is such demand for better oversight of guardians and conservators today. The temptation to treat the relationship as one of benefit to the fiduciary is always present, but guardians who expect oversight are less likely to give in to any opportunity for self‐dealing through the appointment.

We did not attempt to catalogue the extent to which any branch of state government in Massachusetts has indicated a willingness to take on the responsibility and cost of providing guardianship to at‐risk individuals. The past ten years have been discouraging in that respect. There may be many reasons for the reluctance of any branch of government to accept the responsibility for a public guardian, but concerns about cost are high on the list. It is hoped that the cost studies that have been discussed in this Report, showing remarkable savings to the state from providing guardians for the most at‐risk segment of the population, will provide the necessary financial incentives.

The first step toward a Public Guardian in Massachusetts is, we believe, support for an appropriate agency—whether that is the Court, the Department of Health and Human Services, or some other entity—to provide an institutional home for the Public Guardian.

Finally, a theme that we could have included, but decided against, is the professionalization of guardianship. States that have invested in comprehensive public guardianship services have gravitated toward certification of guardians, in hopes that the training this requires will ensure the quality of their work. The Institute clearly an strongly supports the trend toward professionalization of guardianship. We also are aware, however, that state governments need to compensate guardians at levels commensurate with professional services in order to staff a Public Guardian with certified professionals.

2. Recommendations.

(1) Massachusetts should establish and fully fund a robust statewide Public Guardian program with appropriate staffing levels, with professional staff to provide person‐centered guardianships for various populations in need of guardians, and with leadership dedicated to reaching out to stakeholders statewide for input on how to continuously improve services for unrepresented, at‐risk individuals.

(2) The Legislature should consider funding the Public Guardian from the state budget for EOHHS; or from an add‐on fee to guardianship petitions filed by institutions, such as hospital and nursing homes; or from a dedicated state trust fund with funds from the Executive office of Aging and Independence, including APS, legal assistance, state appropriations and outside contributions. (With respect to the add‐on fee, currently it costs nothing to file a petition. The fee could be used to fund the Public Guardian directly . It should not, however, be charged to families, who receive little or no benefit from guardianship appointments other than their own.)

(3) Public Guardian Services was established in 2020 to provide an example of how public guardianship can be done in Massachusetts. This organization was created with a state- operated program in mind. The Institute stands ready and able to share the experience and institutional resources that it has gained from five years of immersion in guardianship services for at-risk individuals who don’t have other options, in hopes that this may contribute to timely and effective action to offer this kind of program statewide.

APPENDIX A.

GENERAL TRENDS AND FACTORS IMPACTING THE NEED FOR PUBLIC GUARDIANSHIP

Although there is a general consensus in the literature of a growing need for public guardianship, there has been relatively little research regarding the specific numbers of individuals in need or the relative costs and benefits of various models of providing public guardianship services. The studies and reports that do exist are generally specific to individual states and do not employ any standard methodologies making it difficult to compare or extrapolate from them. A 2010 study by the National Center for State Courts (NCSC) used the data from just four states to estimate that there are approximately 1.5 million active pending adult guardianships, but with a range from 1 million to 3 million possible. The report points out that there is no standard tracking among states and, for our purposes, no consistent differentiation between private and public guardianships.

Despite the relative lack of evidence specific to public guardianship, there are well established national trends regarding a growing need for adult guardianship that are applicable when considering the specific need for public guardianship in Massachusetts. These trends reflect the sources of those vulnerable populations most often found to be indigent, insufficiently capacitated and in need of guardianship services.

Unfortunately, many indigent adults in need of guardianship fall into more than one of these general trend categories.

A 2010 report from the Conference of State Court Administrators posed the following question.

An increasing number of persons with diminished capacity are poised to transform American institutions, including the courts. What can state courts do to prepare to meet this challenge?

While this report focuses on the expanding burdens on probate and criminal courts, many public and private institutions will also be challenged to meet the growing need for services and protections for these vulnerable populations. This and other reports commonly identify four specific demographic shifts contributing to the increase. These include an aging population supported by increased longevity, growing awareness of mental illness and intellectual and developmental disabilities, military service- related disabilities, and the consequences of advances in medical treatment.

An Aging Population

The greatest contributor to the number of people with diminished capacity is the aging population and increased longevity along with age-related degenerative disease and disability. The US Census Bureau in a 2020 report, predicts that in the year 2030 all baby boomers will be older than 65 years of age, with one in every five Americans at retirement age. In 2034, older adults will outnumber children for the first time.

The number of people 85 years and older is expected to nearly double by 2035 (from 6.5 million to 11.8 million) and nearly triple by 2060 (to 19 million people).

Of particular concern are the trends related to Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Association in a 2022 report estimates that 6.5 million Americans age 65 and older are currently living with Alzheimer’s, with 73% of those age 75 or older. By 2050, the number of cases is projected to be 12.7 million. Racial disparities in the prevalence of Alzheimer’s and other dementias (Blacks twice the rate of Whites, Hispanics one and a half times the rate of Whites) are exacerbated by many other social determinants of health that place these adults at much higher risk.

For example, in 2021, the national poverty rate for people ages 65 and over was 10.3% with adults living in rural settings at higher risk versus metropolitan areas.vi Persons without means to afford private guardianship and living in rural areas in which services and settings are limited will be among the most difficult populations to serve.

Finally, the tremendous physical, emotional and financial toll experienced by family and friends in the role of caregivers means that many of these elders suffering from dementia will outlive their caregivers or their caregivers will, at some point, simply be unable to continue to accept responsibility.

According to USA Facts, the 65+ population in Massachusetts was the fastest growing age group from 2010 to 2022, growing by 39%. During that period, the percentage of the population age 65+ increased from 13.8% of the population to 18.1% This population impacts the growing numbers of retirements and demand for health services.

Of particular concern, 135,000 people, or 11% of adults aged 65 and older, are living with Alzheimer’s disease in Massachusetts.1, 2 16.6% of people aged 45 and older have subjective cognitive decline.2 Just the cost of Alzheimer’s disease to Massachusetts’ Medicaid program is estimated at $2.2 billion in 2024.1, 2 The prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease is projected to increase 25% over the next decade.3

Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders

The combined impact of the opioid crisis and the COVID pandemic have shone a bright light on the prevalence of mental illness and substance use disorders (SUD) in the United States. Both mental illness and SUD contribute to the increasing numbers of unrepresented at-risk adults. In 2020, there were an estimated 52.9 million adults (21%) aged 18 or older in the United States with mental illness. Of these, an estimate of 14.2 million (5.6%) are suffering serious mental illness.

An estimated 26% of Americans ages 18 and older – about 1 in 4 adults – suffers from a diagnosable mental disorder in a given year. Approximately 9.5% of American adults over the age 18 will suffer from a depressive illness (major depression, bipolar disorder, or dysthymia) each year. Many people suffer from more than one mental disorder at a given time. In particular, depressive illnesses tend to co-occur with substance abuse and anxiety disorders.

Over half (54.7%) of adults with a mental illness do not receive treatment, totaling over 28 million individuals. Almost a third (28.2%) of all adults with a mental illness reported that they were not able to receive the treatment they needed. 42% of adults with acute mental illness (AMI) reported they were unable to receive necessary care because they could not afford it.

Although somewhat lower, the prevalence of substance use disorders is also a primary risk factor for unrepresented at-risk adults. In 2020, 40.3 million people aged 12 or older (or 14.5%) had an SUD in the past year, including 28.3 million with alcohol use disorder, 18.4 million with an illicit drug use disorder, and 6.5 million with both alcohol use disorder and an illicit drug use disorder. The vast majority of individuals with a substance use disorder in the U.S. are not receiving treatment. 15.35% of adults had a substance use disorder in the past year. Of them, 93.5% did not receive any form of treatment.

Finally, an estimated 6.7% of adults aged 18 or older in 2020 (or 17.0 million people) suffered from both amental illness and an SUD, with 2.2% (or 5.7 million people) experiencing serious mental illness with an SUD in the past year. Among those with a serious mental illness, two thirds (66.4%) of adults received either substance use treatment at a specialty facility or mental health services in the past year (66.4%), but only 9.3% received both services.

Mental health and substance abuse disorders place great stress on families and support networks, leaving many unable to cope with the demands of caring for a family member suffering mental illness, substance abuse disorder or some combination. Barriers in accessing treatment further contribute to that stress and the potential for an individual to become unrepresented as an at-risk adult.